On May 20th, the CDC released an investigation notice linking a nationwide outbreak of Salmonella to backyard poultry flocks. Here’s what you need to know.

Reported Illnesses and Hospitalizations Relatively Low

To date, the CDC confirms 163 illnesses and 34 hospitalizations directly linked to Salmonella, presumably contracted from backyard chicken flocks. You may be asking then, in the face of such low numbers, why the concern? The CDC cautions that since many recover from Salmonella, the reported numbers may artificially minimize the true extent of the outbreak.

States Affected

According to the CDC, there have been cases of backyard poultry flock-linked Salmonella reported in 43 states. As of this writing, there have only been 2 cases reported in New York.

About Salmonella

Salmonella is a rod shaped bacterium that lives in the intestinal tracts of animals including dogs, cats, fish, reptiles, birds, goats, cows, and pigs. Infected animals do not have to show signs of sickness. The bacteria is deposited in the environment when infected animals defecate. Other animals that either ingest or get this excrement on their fur, feathers, scales or skin can carry the bacteria around with them. Similarly, produce that is fertilized with Salmonella-contaminated manure can also transmit the bacteria. When humans interact with these contaminated animals (pet, hold, kiss, cuddle, husband, butcher, eat) or eat these plants, they can become infected. According to the CDC, approximately 1.2 million Americans get sick with Salmonella each year. Of those, 23 thousand require hospitalization and about 430 of those cases die. Symptoms of salmonellosis, or infection by the Salmonella bacteria, are diarrhea, fever, vomiting and cramps that commence 12 to 72 hours after exposure. The sickness is almost always self-limiting.

Salmonella in Chicken Yards (and All Barnyards) is Relatively Common

Because Salmonella is a relatively common bacteria, it’s possible that some of your chickens are already harboring the bacteria. If they are, some of that Salmonella bacteria may be getting on your farm fresh eggs…stay with me here…may be getting on your eggs, but there are many things working in your favor to prevent cross infection in you and your family.

- Salmonella, like E-coli, lives in the guts of animals and like E-coli, it can be found in environments where there is animal feces, so we would expect to find Salmonella in any barnyard (or on the hands of any restaurant employee that doesn’t practice good hygiene!) The problem isn’t that it’s there; the problem is that we inadvertently eat it when food isn’t processed or cooked properly.

- Risk of egg contamination by Salmonella increases when the eggs are soiled by manure or yard dirt. Eggs that are allowed to rest in moist, soiled bedding are also more likely to get the contamination on their shells. Eggs collected frequently, before they have a chance to get soiled, are less likely to have significant amounts of contamination.

- If Salmonella is present, it is most likely on the shells of the eggs, not on the inside of them (but more on this below). Provided you’re not eating the eggshells, your risk is low.

- Salmonella needs moisture to live. The airy, roomy housing and the free roaming opportunities that typify the backyard chicken setting are not nearly as conducive to harboring Salmonella infection as are the large, cramped confines of commercial egg producers. If you’re going to take the risk of eating eggs (or any food for that matter), one could make a strong argument that the housing you provide your chickens in your backyard is safer and healthier than those experienced by birds raised in commercial settings.

Should I Wash My Eggs Then?

Before we agree on whether or not we should wash our backyard chicken eggs, we need a refresher on egg anatomy because there are a lot of things that the egg already has in place to naturally stop contamination.

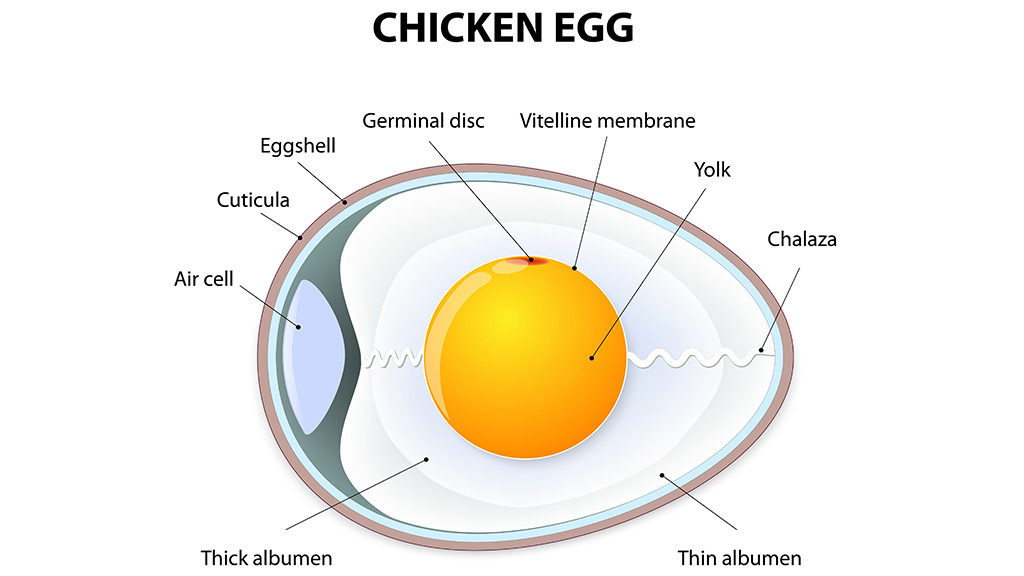

Anatomy of An Egg

The Cuticle

The outer-most portion of the egg is a thin film called the cuticle, sometimes referred to as the bloom. It is a mucous-like protein that has proven antimicrobial properties. Fresh eggs that have not been washed have an ever-so-slight sticky feel whereas store-bought eggs, that have been washed, feel more like a piece of chalk. The difference is that farm eggs have an intact cuticle whereas the cuticle in store eggs is absent, a casualty of the washing process.

The Shell

The next part of the egg is the shell. It is comprised of two layers, both of which have some porosity, but which also have antimicrobial properties. The porosity part is significant consideration in the washing debate discussed further down.

Egg White or Albumen

Next is the thin and thick egg white or albumen. The difference between the two is glaring in fresh eggs. In a fresh egg, the thin layer spreads out around the thick layer, which sits in a stiff mound surrounding the yolk. In store bought eggs, the difference between the thin and thick layer is almost indistinguishable because store eggs are much older than fresh eggs and the protein in the thick portion has had time to degrade. When you crack a store egg into a pan the yolk stands in the middle of a thin puddle of both kinds of albumin which have merged into one because of age.

Egg Whites Have Three Natural Defenses Against Bacteria

Egg whites have three important defenses against bacteria. Firstly they have an impressively high PH of around 9.5. That’s 500 times more alkaline than water. Bacteria have a very difficult time growing in such a high alkaline environment. Secondly, egg whites contain a substance called conalbumin which binds iron leaving any potential bacteria in need of an essential growth mineral. Lastly they contain an enzyme called lysozyme, which as its name suggests, has the ability to lyse or break open bacteria, essentially killing them.

Join A Local Backyard Chicken Group

Did you know that the Facebook group, Rockland Backyard Chicken, has more than 800 members. The group is welcoming, knowledgeable and supportive. Members help one another with things like flock housing, chicken adoption, local ordinances, and more. Click the link and request membership to this great community!

To Wash or Not Wash Your Eggs

Now let’s talk about why washing your eggs is probably a bad idea. When eggs are laid, the inside contents are hot, the same temperature as the inside of a chicken, but after the egg sits in the nest box awhile, it cools and the warmer contents inside contract leaving a slightly negative air space inside the shell. When moisture gets on the egg surface, the negative air space inside the egg pulls on the surface water through the porous shell. By trying to wash off the Salmonella on your eggshell, you’ve actually created a perfect scenario for it to be drawn inside the egg. Moreover any detergents that you’ve used in the washing process have probably compromised or destroyed the cuticle and potentially increased the porosity of the eggshell, both of which increase the chances that the egg will be contaminated with bacteria. To clean eggs, the CDC recommends rubbing dirt off eggs using a dry abrasive like sandpaper.

Why Europe Doesn’t Refrigerate Its Eggs

Interesting trivia point: those of you that have traveled to Europe have probably noticed that the eggs there are often not refrigerated. This is because European eggs are not washed. That is to say, they have an intact cuticle, haven’t had their shells covered with water (the major way Salmonella enters the egg), and are at less risk for contamination. In America, the USDA requires farmers to wash their eggs, but these commercial cleaning assemblies essentially shower all the eggs in whatever dirt was on any one of them. It’s almost the equivalent of a big bathtub shared by hundreds before the water is changed. Refrigeration is essential to U.S. produced eggs because they have been put at higher risk of exposure to harmful bacteria.

How To Prevent My Chickens From Getting Salmonella

- You’re not going to prevent your chicken from getting Salmonella; he or she probably already has it. What you’re going to do is ensure that the meat or eggs you harvest from your chickens is properly handled and cooked.

- It might be considered overkill, but you could vaccinate your birds against Salmonella. This is done in Europe, but the vaccines do not protect against all forms of the bacteria. Birds initially require a dose of vaccine every week for three to four weeks and then a booster vaccine every year. Animal Medical of New City does not carry the Salmonella vaccine or administer it.

- Collect eggs frequently. Eggs that spend more time in the hen house are likely to get soiled.

- Only use wood shavings in nest boxes. Wood shavings absorb moisture and are more likely to keep eggs dry.

- Keep nest boxes high. Make sure that hens can’t roost over them and defecate into them.

- Pay attention to hens with soiled vents. These chickens may be sick and a source of contamination.

- Clean the eggs using a dry abrasive like sandpaper.

- If eggs must be washed, make sure that the water is warm. Warm water will cause the contents of the egg to expand and push against the shell, decreasing the likelihood that bacteria will enter into the egg. Detergent is not necessary.

- Keep the surface of eggs dry. If you choose to refrigerate your eggs, be careful when you take them out and leave them on the counter. They may ‘sweat’ in warm weather. The surface water can allow bacteria on the egg to seep inside.

Give Your Dog and Cat An Egg

If you have backyard chickens, you probably have enough eggs to share with your pets. Eggs are a perfectly safe food for both cats and dogs to eat, provided that they are cooked (not a concern about Salmonella so much as a concern about nutrition. Raw egg whites contain a protein known as avidin, which binds with biotin in the intestines and prevents the dog or cat from absorbing it). We recommend the following Martha Stewart recipe (see below) for the perfect hard boiled egg that can be served to both pets and humans! You’ll love how fragrant it smells and how creamy it is to eat!

Perfect Hard-boiled Egg

Place eggs in a pan of water, bring water to a boil, and then immediately turn off heat. Cover pot and allow eggs to steep for 12 minutes. When finished, plunge eggs into a bowl of ice water. The ice water immediately cools the eggs, stops the cooking process, and creates a jacket of steam around the egg that allows them to be peeled easily. Note: Only use eggs that have aged a week or more if you plan to hard boil them, otherwise they will be difficult to peel. Remember that eggs should sink when submerged in water. Eggs that float are bad and should be discarded.